Project leaders: Dr Benoit Smeuninx and Professor Mark Febbraio

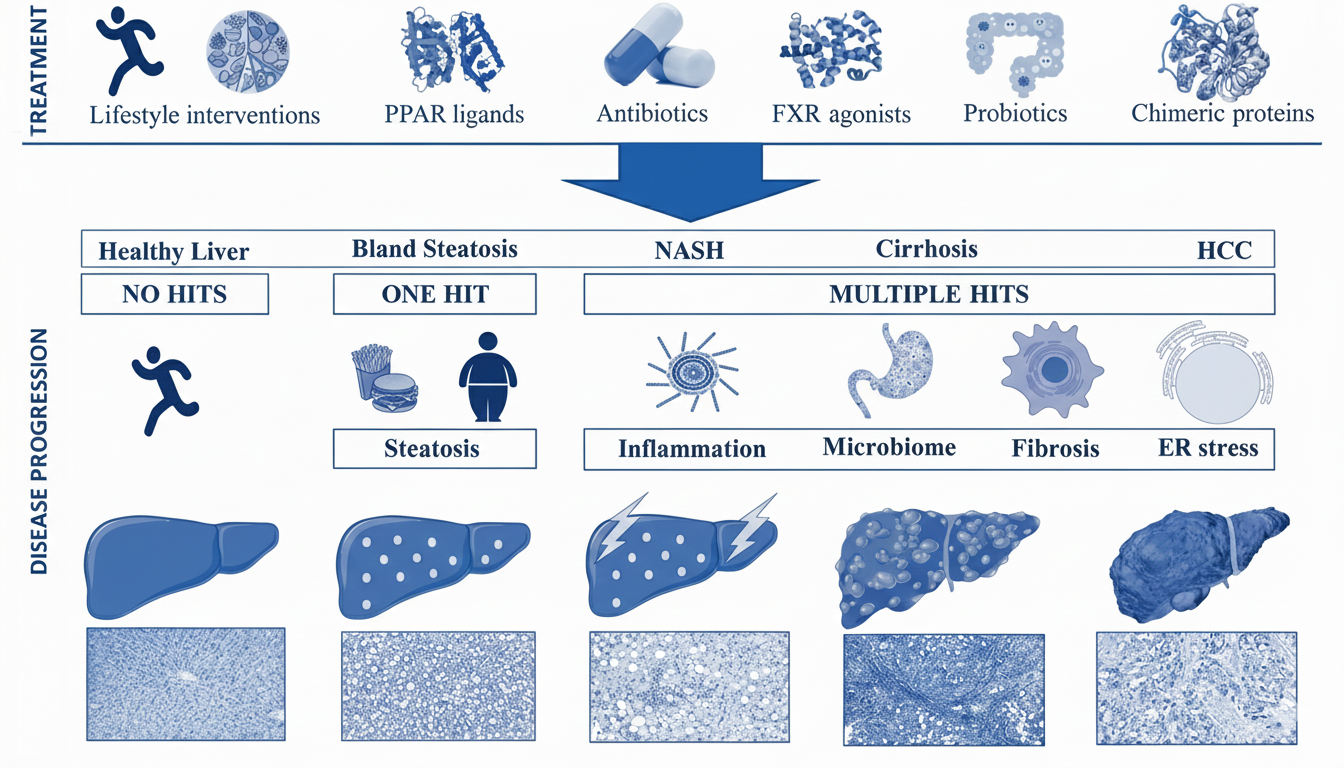

Metabolically-dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) has become a global health crisis, affecting 25 per cent of the world's population. This condition encompasses a spectrum of liver abnormalities ranging from simple fat accumulation (bland steatosis) through to life-threatening liver cirrhosis and cancer.

Understanding a silent epidemic

Many people have some degree of fat in their liver without knowing it. In its mildest form — bland steatosis — this fat accumulation is relatively harmless. However, when inflammation or cellular stress is added to the mix, the condition transforms into metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), a more aggressive disease characterised by liver inflammation and damage.

The most concerning question is how MASH progresses to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) — the most common type of liver cancer. Understanding this transition is crucial for developing treatments that can stop the disease before it reaches this life-threatening stage.

The progression puzzle

MASH doesn't develop from a single cause. Multiple "hits" to the liver — poor diet, obesity, inflammation, changes in gut bacteria, cellular stress — accumulate over time, progressively damaging liver tissue. Some individuals develop cirrhosis and cancer, whilst others with seemingly similar risk factors don't progress beyond earlier stages. Why?

Figure: Schematic showing the progression from healthy liver through bland steatosis, NASH, cirrhosis, to HCC. The top shows treatment approaches (lifestyle interventions, PPAR ligands, antibiotics, FXR agonists, probiotics, chimeric proteins). The bottom shows disease mechanisms: healthy liver requires "no hits"; bland steatosis requires "one hit" (steatosis from diet/obesity); NASH, cirrhosis and HCC require "multiple hits" (inflammation, microbiome changes, fibrosis, ER stress). Histological images show progressive tissue damage at each stage.

Our research approach

We're using the MUP-uPA transgenic mouse model, which closely mimics human disease progression from MASH through to HCC. This model allows us to explore several mechanisms that might catalyse the progression to liver cancer, including:

- Inflammation pathways

How chronic liver inflammation drives tissue damage and cancer development. - Metabolic stress

The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in disease progression. - Microbiome changes

How alterations in gut bacteria influence liver disease. - Fibrosis mechanisms

Understanding how liver scarring accelerates cancer risk.

Identifying early warning signs

Beyond understanding disease mechanisms, we're assessing specific circulatory markers — molecules detectable in blood samples — that could serve as biomarkers for aggressive HCC development. These biomarkers could enable:

- Earlier detection

Identifying patients at high risk before cancer develops - Non-invasive monitoring

Tracking disease progression through blood tests rather than liver biopsies - Treatment stratification

Determining which patients need more aggressive interventions

Testing potential treatments

Our research is evaluating multiple therapeutic approaches that could prevent or slow MASH progression:

- Lifestyle interventions

Understanding how exercise and dietary changes modify disease pathways at the molecular level. - PPAR ligands

Drugs that modulate fat metabolism and inflammation. - FXR agonists

Compounds that reduce liver fat and inflammation. - Antibiotics and probiotics

Targeting the gut-liver axis to reduce harmful bacterial products reaching the liver. - Chimeric proteins

Novel engineered therapeutics, including IC7Fc, that could address multiple disease pathways simultaneously.

Why this research matters

With MAFLD affecting one in four people globally and MASH cases rising alongside obesity rates, the need for effective treatments is urgent. Currently, there are no approved drugs specifically for MASH, and treatment options for HCC remain limited once the cancer has developed.

By understanding the precise mechanisms driving progression from simple steatosis to cancer, we can identify intervention points where treatments could halt or reverse disease — potentially preventing thousands of cases of liver cancer each year.

Next steps

Our ongoing work focuses on:

- Validating biomarkers in human cohorts to enable clinical translation.

- Testing combination therapies that address multiple disease mechanisms.

- Understanding individual variation in disease progression to enable personalised treatment approaches.

- Developing predictive models that identify high-risk patients who would benefit most from early intervention.

This research aims to transform MASH from a progressive, untreatable condition into one where we can predict who's at risk, intervene early, and prevent progression to cirrhosis and cancer.